Before we get to today’s episode on Braille music notation, we have an interesting comment from a reader on this topic for you.

Stay tuned and join us in welcoming Matthias Leopold!

Don’t forget! You still have plenty of time to send us your personal comments on music notation.

Simply send them to braille200@livingbraille.eu

Comment from Matthias Leopold

Hello everyone,

As a sighted person, I am not personally affected by this central issue, but I would like to share my perspective on it:

In my opinion, Braille music notation has a surprisingly and strikingly high visual aesthetic for sighted people. It makes extensive use of symmetries, deliberate asymmetries, clusters, etc. I can only speculate about the reasons for this. One reason could be that Louis Braille grew up with raised symbols and was therefore familiar with this type of aesthetic and tried to transfer it to Braille music notation. From a purely technical perspective, as one might develop when learning the symbols according to their meaning, this dimension may not be perceived and may not be important for understanding the script. In any case, these aesthetic principles make the script fairly easy to read for sighted people, which would not be the case with a different assignment of symbols.

However, in Braille music notation, the assignment of symbols is actually very, very well thought out and meets fairly high standards, as it must. I don’t think there is actually much leeway for an optimal assignment of symbols to meanings. Louis Braille found a very good solution here. By this I mean that reassigning certain symbols, especially the musical symbols, would have a very significant impact on the internal structure. I think that quite a few unexpected problems could arise as a result.

Of course, alternative assignments can be discussed, and such discussions can provide important impetus. However, it seems to me that the existing system is very well suited to complex requirements.

Best regards

Matthias Leopold

Episode 3:

Polyphonic Music

In print notation, piano music is written on two staves: one for the left hand and one for the right hand, aligned vertically. The measures (bars) are divided so that the notes of both hands line up exactly. It’s the same with orchestral scores: each part is written on its own staff, but everything that sounds at the same time is aligned vertically.

In braille music notation, however, each part is written separately. The piece is divided into sections — for example, the first violin for 16 bars, then the second violin for 16 bars, and so on. This means that the music is no longer aligned the way it sounds simultaneously; instead, the performer has to put it together mentally. For piano, there are special signs that indicate whether the notes belong to the right hand or the left hand, so the performer always knows which hand is meant.

But on the piano, a single hand can play several notes at once — chords. In print notation, these are written stacked in one staff. But how can such things be represented linearly in braille?

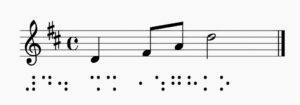

Of course, Louis Braille devised a solution. After all, he himself was both a pianist and an organist. To represent chords, braille music uses interval signs. After a note, additional signs indicate how much higher the simultaneously sounding notes are.

For a third (three scale degrees higher), the sign is dots 3-4-6 (⠬, the digit 0 in computer braille).

For a fifth (five scale degrees higher), the sign is dots 3-5 (⠔, the asterisk in computer braille).

Thus, a C major chord in quarter notes (crotchets) is written as: ⠹⠬⠔

⠹ (dots 1-4-5-6) for C as a quarter note (crotchet),

⠬ (dots 3-4-6) for a simultaneous note a third higher,

⠔ (dots 3-5) for another simultaneous note a fifth higher — i.e. C–E–G.

There is one more convention in piano braille:

For the right hand, the highest note of the chord is written, and the interval signs show the notes below it.

For the left hand, it’s the opposite: the lowest note is written, and the interval signs indicate the notes above it.

There could also be a chord like C–E-flat–G, and of course the notes in a chord don’t all have to be of the same duration. Naturally, Louis Braille devised a method for these situations as well — but we’ll leave that aside for now.

That’s already a lot of information about braille music. But to play many pieces, one needs to be able to read and write even more notation.

In the next episode, you’ll find out where you can learn more.

Polyphonische Ästhetik

Bevor wir zu unserer heutigen Folge zur Braille-Notenschrift kommen, haben wir dieses mal einen interessanten Kommentar eines Lesers zu diesem Thema für euch.

Seid gespannt und begrüßt mit uns ganz herzlich Matthias Leopold!

Nicht vergessen! Ihr habt immernoch genug Zeit, um uns euren persönlichen Kommentar zur Notenschrift zu schicken.

Ganz einfach an braille200@livingbraille.eu

Kommentar von Matthias Leopold

Hallo zusammen,

Ich bin als Sehender von dieser zentralen Problematik selbst nicht betroffen, würde aber gern meine Perspektive dazu darlegen:

Die Braillenotenschrift hat meiner Meinung nach eine für Sehende überraschend und auffallend hohe optische Ästhetik. Sie arbeitet viel mit Symmetrien, gezielten Asymmetrien, Verklumpungen usw. Über die Gründe kann ich nur spekulieren. Ein Grund könnte sein, dass Louis Braille mit Zeichen-Reliefs aufgewachsen ist und darum mit dieser Art von Ästhetik vertraut war und versucht hat, diese auf die Braillenotenschrift zu transportieren. Aus einer rein technisch inhaltlichen Wahrnehmung, wie man sie vielleicht entwickelt, wenn man die Zeichen ihrer Bedeutung nach lernt, wird diese Dimension vielleicht nicht wahrgenommen und ist vielleicht auch nicht von Bedeutung zur Erfassung der Schrift. In jedem Fall ist die Schrift durch diese ästhetischen Prinzipien für Sehende ziemlich gut lesbar, was bei einer anderen Belegung nicht der Fall wäre.

Aber: In der Braillenotenschrift ist die Belegung der Zeichen tatsächlich sehr, sehr durchdacht und wird ziemlich hohen Anforderungen gerecht und muss ihnen auch gerecht werden. Es gibt denke ich dabei tatsächlich gar nicht viel Spielraum für eine optimale Belegung der Zeichen mit Bedeutung. Louis Braille hat hier eine sehr gute Lösung gefunden. Damit meine ich, dass eine Umbelegung bestimmter Zeichen, und zwar insbesondere die der Notenzeichen, sehr große Folgewirkungen auf das innere Gefüge hätte. Ich denke, dass dabei ziemlich viele unerwartete Probleme auftauchen könnten.

Natürlich kann man über alternative Belegungen diskutieren und solche Diskussionen können wichtige Impulse geben. Mir erscheint jedoch, dass das bestehende System sehr gut auf komplexe Anforderungen abgestimmt ist.

Beste Grüße

Matthias Leopold

Folge 3:

Mehrstimmige Musik

Klaviernoten sind in Schwarzschrift für die linke und rechte Hand in getrennten Notensystemen geschrieben, die übereinander stehen. Die Takte sind auch so eingeteilt, dass sie genau übereinanderstehen. So ist das auch bei Partituren für Orchester. Jede Stimme steht in einem eigenen Notensystem, aber alles, was gleichzeitig erklingt, steht auch untereinander.

In Braille wird jede Stimme einzeln aufgeschrieben. Das Stück wird dazu in Abschnitte eingeteilt., z. B. Erst 16 Takte erste Geige, dann 16 Takte zweite Geige u. s. w. Dann steht nicht mehr alles, was man gleichzeitig hört, untereinander. Das muss man sich im Kopf selbst zusammenbasteln. Für die rechte und linke Hand beim Klavierspielen gibt es besondere Zeichen; so weiß man immer, für welche Hand die Noten sind.

Aber auf dem Klavier kann man mit einer Hand mehrere Töne zugleich spielen: akkorde. Die stehen in Schwarzschrift in einem Notensystem übereinander. Wie will man so etwas denn in Braille linear nacheinander schreiben.

Natürlich hat sich Louis Braille auch dafür etwas ausgedacht. Schließlich war er Pianist und Organist. Zum Darstellen von Akkorden benutzt man in Braille “Intervallzeichen”. Man schreibt nach einer Note für die gleichzeitig erklingenden Töne jeweils ein Zeichen dafür, wie viel höher der Ton ist.

Für eine Terz (drei Töne Unterschied) ist das Punkte 3 4 6 (⠬, wie die 0 in Computerbraille). Für eine Quint (fünf Töne Unterschied) ist es Punkte 3 5 (⠔, Stern in Computer-Braille). Ein C-Dur-Akkord aus Viertelnoten sieht dann so aus: ⠹⠬⠔ (Punkte 1 4 5 6 für das C als Viertel, Punkte 3 4 6 für einen gleichzeitigen Ton eine Terz höer und Punkte 3 5 für einen weiteren Ton eine Quint höher), also C E G.

Für Klaviernoten gibt es noch eine Besonderheit: für die Rechte Hand wird der höchste Ton des Akkords geschrieben und die Intervallzeichen zeigen die Töne darunter an. Für die Linke Hand ist es umgekehrt.

Es könnte auch einen Akkord C ES G geben und die gleichzeitig erklingenden Töne müssen auch nicht gleich lang sein. Klar hat sich Louis Braille auch dafür etwas ausgedacht. Aber das lassen wir hier weg.

Das war bisher richtig viel Information über Braille-Noten. Aber für viele Musikstücke muss man noch viel mehr an Notenschrift schreiben und lesen können.

In der nächsten Folge erfahrt Ihr, wo Ihr das alles nachlesen könnt.

useful links:

Read all articles on: livingbraille.eu

Contact us with your contributions, ideas and questions by: braille200@livingbraille.eu

Social media: Braille 200 on Facebook