October 1 is International Music Day.

That’s why we’re spending the whole week looking at a writing system that was also invented by Louis Braille: Braille music notation.

Today: The introduction

Louis Braille invented Braille – that much is clear. But there are many different scripts that can be represented using the six dots: mathematics, Arabic, Chinese, and chess diagrams. This is because the dot combinations can be defined as desired.

Louis Braille was a musician. He played the piano and was an organist in two Parisian churches. In order to learn pieces of music, one needed sheet music then as now. The Braille alphabet was still banned at the Paris school for the blind; in 1828, teachers still believed that blind people should not use a script that sighted people cannot read. At that time, Louis Braille was already inventing his musical notation.

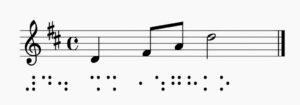

Here, too, he used symbols consisting of six dots, but they have nothing to do with the Braille alphabet. This can be quite confusing when symbols that you are used to reading as letters suddenly mean something completely different.

For example, the note E is not the Braille letter E (⠑), but looks like an F (⠋), and so on.

The black-print notes used by sighted people are a two-dimensional graphic system. They are essentially analog, with high notes appearing higher up and low notes lower down. Long notes take up more space than short ones. Notes that sound simultaneously are placed one below the other in the same position. Even in scores for many voices, everything that is heard simultaneously is placed one below the other.

Braille devised a completely different system for musical notation: all symbols are placed one after the other—in a linear fashion. This is a completely unique and independent musical notation system that Braille himself devised. Unlike the alphabet, there is no Braille symbol for each letter. A Braille note can look very different in different contexts and can also consist of several Braille symbols.

This means that you cannot immediately “see” how the music sounds. You have to decode it and translate it into the corresponding sounds yourself. But that’s OK, because as a blind musician you can’t play from sheet music anyway, as you need your hands to read and to play music. It’s a little different when it comes to singing. Some blind people can read the notes with one hand and the lyrics with the other, enabling them to sing from sheet music.

Normally, however, blind people learn pieces of music by heart. This has advantages because you can become independent of the sheet music and play freely. But if you have a blackout, you can’t quickly look up how the piece continues in the sheet music. And you always need time to prepare a piece.

You will learn exactly how Braille music notation works in the next episodes.

Musikwoche: Einführung

Am 1. Oktober ist der Weltmusiktag, the International Music Day.

Darum beschäftigen wir uns die ganze Woche mit einer Schrift, die auch von Louis Braille erfunden wurde: Die Braille Notenschrift.

Heute: Die Einführung

Louis Braille hat die Brailleschrift erfunden – klar. Aber es gibt ganz verschiedene Schriften, die sich mit den sechs Punkten darstellen lassen: Mathematik, Arabisch, Chinesisch oder Schachdiagramme. Denn die Punktkombinationen lassen sich beliebig definieren.

Louis Braille war Musiker. Er spielte Klavier und war in zwei Pariser Kirchen Organist. Um sich Musikstücke anzueignen, brauchte man damals wie auch heute noch Noten. Das Braille-Alphabet war in der Pariser Blindenschule noch verboten; die Lehrer waren 1828 noch der Meinung, dass Blinde nicht eine Schrift nutzen sollen, die Sehende nicht lesen können; zu dieser Zeit erfand Louis Braille bereits seine Notenschrift.

Auch hier nutzte er dafür Zeichen aus sechs Punkten, aber die haben mit dem Braille-Alphabet rein gar nichts zu tun. Das kann ganz schön verwirren, wenn Zeichen plötzlich etwas ganz anderes bedeuten, die man bisher gewohnt ist, als Buchstaben zu lesen.

Die Schwarzschrift-Noten der Sehenden sind ein zweidimensionales grafisches System. Sie sind quasi analog, denn hohe Töne stehen weiter oben und tiefe Töne weiter unten. Lange Noten nehmen mehr Platz ein als kurze. Töne, die gleichzeitig erklingen, stehen untereinander an der gleichen Stelle. Auch in Partituren für viele Stimmen steht alles untereinander, was gleichzeitig zu hören ist. Braille hat für die Notenschrift ein völlig anderes System erdacht: Alle Zeichen stehen hintereinander – also linear. Das ist eine ganz eigene unabhängige Notenschrift, die Braille selbst erdacht hat. Es gibt nicht wie im Alphabet für einen Buchstaben ein Braille-Zeichen. Eine Braille-Note kann in verschiedenen Zusammenhängen ganz anders aussehen und auch aus mehreren Braille-Zeichen bestehen. So kann man nicht gleich “sehen”, wie die Musik klingt. Man muss den Code entschlüsseln und ihn selbst in die entsprechenden Klänge umsetzen. Das ist aber OK, denn als blinde Musikerin oder blinder Musiker kann man sowieso nicht vom Blatt spielen, denn man braucht die Hände zum Lesen und zum Musizieren. Etwas anders ist es beim Singen. Es gibt Blinde, die mit einer Hand die Noten und mit der anderen den Text lesen und so vom Blatt singen können. Normalerweise lernen Blinde die Musikstücke aber auswendig. Das hat Vorteile, weil man sich vom Notenblatt unabhängig machen und frei spielen kann. Hat man aber einen Blackout, kann man nicht mal schnell in den Noten nachschauen, wie das Stück weitergeht. Und man braucht immer Zeit, um ein Stück vorzubereiten. Wie die Braille-Notenschrift genau funktioniert, erfahrt Ihr in den nächsten Folgen. Read all articles on: livingbraille.euuseful links:

Contact us with your contributions, ideas and questions by: braille200@livingbraille.eu

Social media: Braille 200 on Facebook