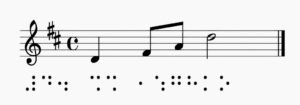

Once you have finally mastered all the peculiarities and possibilities of this musical notation, how do you actually work with it in practice? Today, two professional musicians tell us how Braille music notation opened the door to professional independence for them, how the technical challenges have changed over time, how much joy the notation brings them, and why it is also worthwhile for young blind musicians to learn the intricacies of this complex system.

Bernadette Schmidt

My name is Bernadette Schmidt. I have been playing music using Louis Braille’s musical notation since my youth. My piano teacher at the school for the blind in Karl-Marx-Stadt, now Chemnitz again, repeatedly practiced with me how I could practice and learn literature with the help of musical notation. Ms. Vogel was blind herself and had learned musical notation from a young age and always worked with it, even studying school music with recorder and flute as minor subjects. It was different with my organ teacher, Ms. Elfriede Pätzold. She simply put herself in my shoes and selected pieces that she thought would be easy to memorize. Of course, it was then a big leap from lessons alongside school and vocational training to studying music in Görlitz. There, I had to learn several pieces in parallel in a relatively short time. In addition, there were a number of choral works. Music notation was not as advanced as it is today, and copying sheet music was the order of the day. Looking back, it was not easy to persevere; it took a lot of nerve. I was very fortunate to be able to start studying church music in Görlitz with two preliminary semesters. This gave me time to get used to everything and I was able to complete various subjects one by one. I always had to find people to dictate sheet music to me. This was not only the case during my studies, but also accompanied me well into my professional life. How I longed to be able to open a choir book, browse through it, and find choir literature for my choir. And with electronic music notation programs, it’s possible today! I am still deeply grateful for this and always enjoy it. I particularly enjoy being able to sing along in an ensemble or choir myself, with the music and lyrics in front of me. I remember well how tedious it used to be to listen to choir voices.

Music notation opened the door to an independent and self-determined professional life in church music for me. Of course, as a blind cantor, I had to work hard for it. However, my colleagues and the congregation have always fully recognized and appreciated my abilities. I owe this to the invention of Louis Braille and, not least, to all those who are committed to developing and disseminating musical notation for the blind. Thank you all from the bottom of my heart!

I can only encourage all young Braille readers who make music, in whatever way, to embrace this medium. Even in jazz or popular music, which relies heavily on improvisation, an understanding of musical notation and the ability to work out melodies, chord progressions, and the like independently is an invaluable advantage and makes it much easier to play music together with sighted musicians. It doesn’t always have to be knowledge of the entire set of rules. Often, a fraction of what you need for your area is enough.

I am delighted that Braille is being highlighted in so many different ways this year and I very much hope that it will once again receive more attention in school lessons in all its diversity!

Erika Reischle-Schedler

Erika Reischle-Schedler writes: A complex Beethoven sonata on the piano or Reger’s choral fantasies on the organ, to name just two examples, cannot be rehearsed without Braille music and therefore cannot be performed by a blind musician. It may be possible to learn a single melody part in singing or on a melodic instrument rudimentarily by ear, but even then, the subtle details can only be grasped with Braille music.

With Braille music notation, I can (assuming I have a printed book):

– On the piano: read one system with my right hand and the other with my left hand at the same time, giving me an idea of the nature of a composition and thus at least a hint of an overview, in individual sections, of course.

– On the organ: play the slow movement of a thorough bass piece with the bass on the organ pedal and the chords in the right hand, while the left hand reads the bass and the corresponding figures. This is the only way I know of playing music on a keyboard instrument without having to learn it by heart.

– When singing: I play the melody with one finger and read the lyrics with the finger of my other hand at the same time, which allows me to sing simple pieces sight-reading. Of course, this doesn’t work with complicated pieces, so I have to decide whether I can remember the lyrics or the notes faster and read the other part accordingly.

– In general: I can write all kinds of music myself, have it dictated to me, or compose it myself. In individual cases, I can create my own notation that is suitable for everyday use if, for whatever reason, the official notation does not suit me or if there is no official solution for the requirements I have to meet.

– For conducting tasks: With the help of bar-by-bar notation, I can get an overview of a choir or ensemble piece and have the different entries of the voices directly under my fingers, readable one-to-one.

The only problem is that if I need individual sheet music that 50 other people don’t want, and if it’s more than just three pages, the capacities of the official transcription services still don’t allow me to get the sheet music. When it comes to individual service outside the mainstream, the situation in our country remains sad to this day. Until the bitter end of a musician’s career beyond the age of 70, the struggle for the necessary sheet music remains a faithful companion. When it comes to German-language texts in particular, no foreign library can help, because the programs for texts are only available in the national language (I’ve tried everything).

Musikerinnen berichten

Wie arbeitet man eigentlich ganz konkret mit dieser Notenschrift, wenn man sich endlich mühsam all ihre Eigenheiten und Möglichkeiten angeeignet hat? Zwei professionelle Musikerinnen berichten uns heute, wie die Braillenotenschrift ihnen die Tür zur beruflichen Selbstständigkeit geöffnet hat, wie sich die technischen Herausforderungen im Laufe der Zeit verändert haben, welche Freude ihnen die Schrift bereitet und warum es sich auch für blinde Nachwuchsmusiker lohnt, die Feinheiten dieses komplexen Systems zu erlernen.

Bernadette Schmidt

Mein Name ist Bernadette Schmidt. Seit meiner Jugend musiziere ich mit der Notenschrift von Louis Braille. Meine Klavierlehrerin hat mit mir im Klavierunterricht an der Blindenschule Karl-Marx-Stadt, jetzt wieder Chemnitz, immer wieder geübt, wie ich Literatur mit Hilfe der Notenschrift üben und lernen kann. Frau Vogel war selbst blind und hatte von Jugend auf die Notenschrift gelernt und immer damit gearbeitet, selbst Schulmusik studiert mit den Nebenfächern Block- und Querflöte. Anders war es bei meiner Orgellehrerin Frau Elfriede Pätzold. Sie hat sich einfach in meine Situation hineinversetzt und mir Stücke ausgewählt, von denen sie der Meinung war, dass sie sich gut auswendig lernen lassen. Natürlich war es dann ein großer Sprung vom Unterricht neben Schul- und Berufsausbildung zum Musikstudium in Görlitz. Dort musste ich Parallel verschiedene Stücke in relativ kurzer Zeit erlernen. Dazu kam eine Anzahl von Chorwerken. Die Notenproduktion war lange nicht so fortgeschritten wie heutzutage und das Abschreiben von Noten war an der Tagesordnung. Es war im Rückblick nicht leicht, sich durchzubeißen, kostete viel Nervenkraft. Ich hatte das große Glück, das Studium der Kirchenmusik in Görlitz mit zwei Vorsemestern beginnen zu können. So blieb mir Zeit, mich in alles einzufinden und ich konnte verschiedene Fächer nach und nach abschließen. Immer musste ich Menschen finden, die mir Noten diktierten. Das war nicht nur in der Studienzeit so, sondern begleitete mich weit in mein Berufsleben. Wie hatte ich mich danach gesehnt, einmal ein Chorbuch aufschlagen zu können, um darin zu stöbern und Chorliteratur für meinen Chor dort herauszufinden. Und mit den elektronischen Notenschriftprogrammen ist es heute möglich! Ich bin immer noch zutiefst dankbar dafür und genieße es immer. Besonders viel Freude habe ich, wenn ich selber in einem Ensemble oder auch in einem Chor einfach mitsingen kann und dabei die Noten und den Text vor mir habe. Ich erinnere mich gut, wie mühsam früher das abhören von Chorstimmen war.

Die Notenschrift hat mir das Tor zu einem selbständigen und selbstbestimmten Berufsleben in der Kirchenmusik geöffnet. Sicherlich musste ich als blinde Kantorin viel dafür arbeiten. Ich bin aber im Kollegenkreis und auch in der Gemeinde mit meinem Können immer voll anerkannt und geschätzt worden. Das verdanke ich der Erfindung von Louis Braille und nicht zuletzt allen, die sich in der Entwicklung der Verbreitung der Notenschrift für blinde engagieren. Danke allen von ganzem Herzen!

Alle jungen Blindenschriftleser, die Musik machen, egal auf welche Weise, kann ich nur ermuntern, sich diesem Medium zu stellen. Selbst beim Jazz oder populärer Musik, die viel durch Improvisation lebt, ist ein Verständnis von Noten, das selbständige Erarbeiten von Melodien, Akkordfolgen o.ä. ein unschätzbarer Vorteil und erleichtert das gemeinsame Musizieren mit sehenden Musikern enorm. Es muss ja nicht immer die Kenntnis des ganzen Regelwerkes sein. Oft reicht ein Bruchteil, den man für seinen Bereich brauchen kann, aus.

Ich freue mich, dass die Brailleschrift in diesem Jahr auf so vielfältige Weise in den Fokus gestellt wird und wünsche mir sehr, dass sie in ihrer Vielfalt wieder mehr Beachtung im Schulunterricht findet!

Erika Reischle-Schedler

Erika Reischle-Schedler schreibt: Eine komplexe Beethovensonate am Klavier oder Regers Choralphantasien an der Orgel, um nur 2 Beispiele zu nennen, sind ohne Braille-Noten nicht einstudier- und damit für einen blinden Musiker auch nicht aufführbar. Man mag eine einzelne Melodiestimme in Gesang oder Melodieinstrument rudimentär nach Gehör lernen können, aber selbst da sind die differenzierten Details nur über Braillenoten zu erfassen möglich.

Mit Braillenoten kann ich (ein gedrucktes Buch vorausgesetzt):

– Am Klavier: das eine System mit der rechten Hand, das andere mit der Linken gleichzeitig lesend mir ein Bild von der Beschaffenheit einer Komposition und damit wenigstens eine Andeutung von Überblick verschaffen, in einzelnen Abschnitten natürlich.

– An der Orgel: den langsamen Satz eines Generalbaßstückes mit Baß im Orgelpedal und den Akkorden in der rechten Hand spielen, während die Linke den Baß und die dazugehörigen Bezifferungen abliest. Die einzige mir bekannte Möglichkeit, Musik beim Spiel am Tasteninstrument nicht auswendig lernen zu müssen, sondern abspielen zu können.

– Beim Singen: Mit dem einen Finger die Melodie, mit dem Finger der anderen Hand den Text gleichzeitig lesen und damit bei einfachen Stücken so etwas wie vom Blatt singen zustandebringen. Bei Komplizierten geht das natürlich nicht, hier muß ich entscheiden, ob ich schneller den Text oder schneller die Noten im Kopf behalte und entsprechend den anderen Part ablese.

– Generell: Ich kann Noten aller Art selbst schreiben, sie mir diktieren lassen oder selbst komponieren. Ich kann im Einzelfall eine für mich alltagstaugliche Schrift selbst kreieren, wenn mir die Offizielle entweder aus welchen Gründen immer nicht zusagt oder es für die Anforderungen, die an mich gestellt werden, noch keine offizielle Lösung gibt.

– Bei Leitungsaufgaben: Mit Hilfe von Takt-unter-Takt-Schreibweise kann ich mir einen Überblick über ein Chor- oder Ensemblestück verschaffen und habe eins zu eins ablesbar die unterschiedlichen Einsätze der Stimmen direkt unter meinen Fingern.

Einziges Problem: Wenn ich individuell Noten brauche, die nicht 50 andere auch noch wollen, und wenn es nicht bloß 3 Seiten sind, erlauben mir die Kapazitäten der offiziellen Übertragungsstellen bis heute nicht, die Noten zu bekommen. Für individuellen Service abseits des Mainstream sieht es bis heute traurig aus in unserem Land. Bis zum bitteren Ende einer Musikertätigkeit jenseits des 70. Lebensjahres bleibt der Kampf um erforderliche Noten ein treuer Lebensbegleiter. Wenn es um speziell deutschsprachige Texte geht, kann auch keine ausländische Bibliothek helfen, weil die Programme für Text jeweils nur in der Landessprache zur Verfügung stehen (alles schon probiert).

useful links:

Read all articles on: livingbraille.eu

Contact us with your contributions, ideas and questions by: braille200@livingbraille.eu

Social media: Braille 200 on Facebook