For International Music Day, we not only have the next episode of our series on this topic for you, but also a wonderful feature from the BBC that looks at how braille music notation has influenced blind musicians over the past 200 years.

We wish you lots of joy listening and a very happy International Music Day!

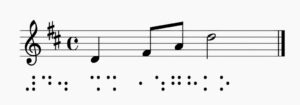

Pitches

So far, we’ve learned about seven notes that can be represented in braille. But a piano, for example, has 88 keys — so there must be more. That’s seven octaves, and each of them has its own name.

When a melody moves from one octave to another, a symbol for the new octave is written. The octave signs are based on braille dots 4-5-6. For example, the sign for the one-line octave is braille dot 5.

And on the piano there are not only white keys, but also black ones — the semitones. If a note is raised by a semitone, a sharp is placed in print notation; in braille it is dots 1-4-6 (⠩, like the number 3 in computer braille). A flat lowers a note by a semitone and in braille it is dots 1-2-6 (⠧, like the number 2 in Euro Braille).

If in the same measure the same note occurs again, but should not be raised or lowered, a natural sign is needed. In braille this is dots 1-6 (⠡, like the number 1 in Euro Braille).

Just like in print notation, the key signature of the whole piece is given at the beginning. For a piece in A major, three sharps are written before the notes: ⠩⠩⠩.

After that, only notes that do not belong to the key need a sharp, flat, or natural sign.

That’s how melodies are written. But what about polyphonic music? You’ll find out in the next part.

The story of Braille music and its impact on blind musicians over the last 200 years

2025 marks 200 years since Louis Braille invented his revolutionary 6-dot tactile writing system for blind people. Braille was also an organist, and he went on to adapt his system into Braille Music, allowing blind musicians to access and study scores like never before.

Award-winning lutenist Matthew Wadsworth travels to France to learn about the origins of Braille Music and explores the impact it’s had on blind musicians over the last 200 years.

Matthew visits the Musée Louis Braille (Braille’s childhood home) in Coupvray, France to learn about Louis Braille’s early life. He also travels to the Institut National des Jeunes Aveugles (The National Institute for Blind Youth) in Paris – the institute for blind students where Louis Braille was a student and teacher. The school still teaches blind students today and organ teacher Alexandra Bartfeld tells Matthew how the institute trained famed blind organists like Jean Langlais, Louis Vierne and Gaston Litaize.

Philippa Campsie, independent researcher into the history of blindness, explains how Charles Barbier’s Night Writing code using raised dots inspired Louis Braille. And Mireille Duhen, from the Valentin Haüy museum, shows Matthew period tactile music scores from the turn of the 19th century.

Internationally acclaimed concert pianist Ignasi Cambra explains at the piano how he uses Braille Music to memorise a score.

Viola player Takashi Kikuchi is a member of Paraorchestra. He recently learned the music for the Virtuous Circle – an orchestral performance of Mozart’s 40th Symphony with additional music by Oliver Vibrans. He discusses the challenges of memorising contemporary music and how he worked with fellow viola player and Assistant Music Director of Paraorchestra, Siobhan Clough, to access the score.

Recorder player and composer James Risdon talks to Matthew about the ways digital Braille Music scores have benefited his career. And Dr Sarah Morley Wilkins from the Daisy Consortium Braille Music project and Jay Pocknell (Project Manager at Sound Without Sight and Music officer at the Royal National Institute for Blind People) discuss their work with music publishers to improve access to Braille Music scores in the digital age.

Alles gute zum Welttag der Musik

Für den offiziellen Musikfeiertag haben wir nicht nur die nächste Folge unserer Textreihe zum Thema für euch, sondern auch einen tollen Beitrag der BBC, der sich damit beschäftigt, wie die Braillenotenschrift blinde Musiker in den letzten 200 Jahren beeinflusst hat.

Wir wünschen euch allen viel Freude beim Zuhören und einen fröhlichen Tag der Musik!

Tonhöhen

Wir haben bisher sieben Töne kennengelernt, die man in Braille darstellen kann. Aber ein Klavier zum Beispiel hat 88 Tasten. Da muss es also noch mehr geben. Das sind sieben Oktaven, die auch alle einen Namen haben.

Wenn eine Melodie von einer Oktav in eine andere wechselt, dann schreibt man ein Zeichen für die neue Oktav. Die Oktavzeichen werden aus den Braille-Punkten 4 5 6 gebildet. Das Zeichen für die eingestrichene Oktav ist zum Beispiel der Braille-Punkt 5.

Und auf dem Klavier gibt es nicht nur weiße, sondern auch schwarze Tasten, die Halbtöne. Ist eine Note einen Halbton höher, dann schreibt man in Schwarzschrift ein Kreuz davor; in Braille ist es das Zeichen mit den Punkten 1 4 6 (⠩, wie die 3 in Computer-Braille). Das b macht eine Note einen Halbton tiefer und ist in Braille Punkte 1 2 6 (V, wie die 2 in Computer-Braille).

Wenn im gleichen Takt noch mal dieselbe Note vorkommt, die nicht höher oder tiefer sein soll, braucht man ein Auflösungszeichen. Das ist in Braille Punkte 1 6 (⠡, wie die 1 in Computerbraille).

Wie bei Schwarzschriftnoten wird die Tonart des gesamten Stücks am Anfang angegeben. Für ein Stück in A-Dur schreibt man drei Kreuze vor den Noten: ⠩⠩⠩.

Dann erhalten nur Töne ein Kreuz, b oder Auflösungszeichen, die nicht zur Tonart gehören.

So schreibt man Melodien, aber was ist bei mehrstimmiger Musik? Das erfahrt Ihr in der nächsten Folge.

Die Geschichte der Braille-Musik und ihr Einfluss auf blinde Musiker in den letzten 200 Jahren

Im Jahr 2025 jährt sich zum 200. Mal die Erfindung des revolutionären 6-Punkt-Tastsystems für Blinde durch Louis Braille. Braille war auch Organist und entwickelte sein System weiter zur Braille-Musik, die blinden Musikern einen völlig neuen Zugang zum Studium von Partituren ermöglichte.

Der preisgekrönte Lautenspieler Matthew Wadsworth reist nach Frankreich, um mehr über die Ursprünge der Braille-Musik zu erfahren und ihren Einfluss auf blinde Musiker in den letzten 200 Jahren zu erforschen.

Matthew besucht das Musée Louis Braille (Brailles Elternhaus) in Coupvray, Frankreich, um mehr über Louis Brailles frühes Leben zu erfahren. Außerdem besucht er das Institut National des Jeunes Aveugles (Nationales Institut für blinde Jugendliche) in Paris – das Institut für blinde Schüler, an dem Louis Braille Schüler und Lehrer war. Die Schule unterrichtet auch heute noch blinde Schüler, und die Orgellehrerin Alexandra Bartfeld erzählt Matthew, wie das Institut berühmte blinde Organisten wie Jean Langlais, Louis Vierne und Gaston Litaize ausgebildet hat.

Philippa Campsie, unabhängige Forscherin zur Geschichte der Blindheit, erklärt, wie Charles Barbiers Nacht-Schreibcode mit erhabenen Punkten Louis Braille inspirierte. Und Mireille Duhen vom Valentin-Haüy-Museum zeigt Matthew taktile Partituren aus der Zeit um die Wende zum 19. Jahrhundert.

Der international renommierte Konzertpianist Ignasi Cambra erklärt am Klavier, wie er Braille-Musik verwendet, um sich eine Partitur einzuprägen.

Der Bratschist Takashi Kikuchi ist Mitglied des Paraorchestra. Vor kurzem lernte er die Musik für „Virtuous Circle“ – eine Orchesteraufführung von Mozarts 40. Sinfonie mit zusätzlicher Musik von Oliver Vibrans. Er spricht über die Herausforderungen beim Auswendiglernen zeitgenössischer Musik und darüber, wie er mit seiner Kollegin, der Bratschistin und stellvertretenden Musikdirektorin des Paraorchestra, Siobhan Clough, zusammengearbeitet hat, um Zugang zur Partitur zu erhalten.

Der Blockflötist und Komponist James Risdon spricht mit Matthew darüber, wie digitale Braille-Noten seiner Karriere zugute gekommen sind. Und Dr. Sarah Morley Wilkins vom Daisy Consortium Braille Music Project und Jay Pocknell (Projektmanager bei Sound Without Sight und Musikbeauftragter am Royal National Institute for Blind People) sprechen über ihre Zusammenarbeit mit Musikverlagen, um den Zugang zu Braille-Noten im digitalen Zeitalter zu verbessern.

useful links:

Read all articles on: livingbraille.eu

Contact us with your contributions, ideas and questions by: braille200@livingbraille.eu

Social media: Braille 200 on Facebook