As promised, today we are continuing our little excursion into Braille music notation.

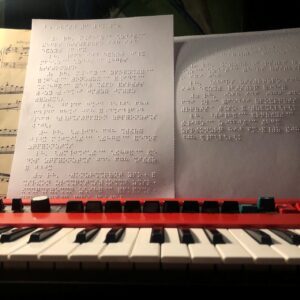

And in addition, Tânia Jordão Cardoso is providing some variety in our pictures today with her great additional picture contribution, which is perfectly suited to the event.

But that’s not all:

For some of us, Braille music notation was and is an important part of our passion and a faithful companion throughout life.

Today, we’ll read a few thoughts on this from Erich Schmid.

Do you also have a special connection to musical notation?

Perhaps, like some of us at “Braille 200,” it caused you sleepless nights before a test?

Feel free to send us your memories and thoughts at braille200@livingbraille.eu and share them with us all here.

But now we don’t want to keep you in suspense any longer and will start with Tânia’s little picture contribution.

Episode 2:

The note names

Why is the musical note A not actually the Braille letter A (⠁)?

Louis Braille had a reason for this. The note names are formed from characters that occupy the square of the upper four dots of the Braille cell: these are the letters D E F G H I and J (⠙⠀⠑⠀⠋⠀⠛⠀⠓⠀⠊⠀⠚).

Braille uses the characters consisting only of the dots on the left-hand side—i.e., dots 1, 2, and 3—for other things; we will find out what those are later. The letters A and B (⠁⠀⠃) belong to these characters.

Braille also needs the characters consisting of two dots next to each other – 1 3, 2 5 and 3 6 (⠉⠀⠒⠀⠤) – for other things.

So the letters D to J stand for the notes C to H.

It is also assumed that Braille knew the note names as Do Re Mi Fa So La Ti Do. And so it makes sense to assign the letter D to the note Do.

In music, notes have different lengths. This must also be expressed in Braille musical notation. To do this, Braille uses the two lower dots 3 and 6 of the Braille cell.

Eighth notes do not have any of these dots. An eighth note C is therefore the Braille letter D (⠙).

Quarter notes are given the additional dot 6. The quarter note C therefore looks like the 4 in Eurobraille (dots 1 4 5 6, ⠹).

A half note gets the additional dot 3. A half note C therefore looks like an N (⠝).

Finally, whole notes get dots 3 and 6, which means that a whole note C looks like a Y (⠽).

And what about 32nd notes?

Dots 3 and 6 can ave multiple meanings: the whole note with dots 3 and 6 looks exactly like the 16th note, the half note like the 32nd note, the quarter note like the 64th note, and the eighth note like the 128th note.

Whether the Braille symbol dots 1 3 4 5 6 (Y, ⠽) is a whole note or a sixteenth note can be determined from the context: only one whole note fits into a 4/4 measure, but 16 sixteenth notes do.

By the way: how do you know when a measure is over? In Braille, the measure line is simply a blank space.

There is another special feature: if there are many fast notes (16th notes or faster) of the same length in succession, you only have to write the dots for the note length on the first one; for the following notes of the same length, you can omit the dots. In a time when writing was only done with a slate, this saved a lot of dots and also made it easier to read.

You can also see from the symbols for pauses that C cannot be the letter C.

The pauses are represented as follows:

Eighth notes and 128th notes = dots 1 3 4 6 (X, ⠭)

Quarter notes or 64th notes = dots 1 2 3 6 (V, ⠧)

Half notes or 32nd notes = dots 1 3 6 (U, ⠥)

Whole or 16th notes = dots 1 3 4 (M, ⠍)

If the letter C were also the note C, then M would be a half C, but it is also a half pause.

There is one thing that looks the same in Braille as in black print notes: the dot. A dot after a black print note or pause extends it by half. In Braille, this is dot 3, which is written after a note. A C that is 3 beats long looks like this: N. (⠝⠄)

In the next episode, you will learn how to write more than just seven notes.

Braille music notation from my childhood to today

I owe many important influences in my life to the ingenious invention of Braille and Braille music notation:

At the school for the blind in Vienna, I was introduced to musical notation and the basics of harmony in music lessons starting at the age of 10.

My piano teacher was so far-sighted that, in addition to learning pieces by ear, he also introduced me to simple exercises in Braille music notation for pieces on the piano and later also on the organ.

Since I aspired to become a music teacher, my knowledge of musical notation was very beneficial, because my instructor at the teacher training college did not give me individual attention due to the large number of students.

There was a small church choir in the parish where I lived, and I was asked to take over as choir director. I performed this voluntary service for about 30 years, and soon I also took on the role of cantor for psalms and hymns during church services.

Today’s technical possibilities make it easier to translate pieces of music into Braille music notation, and I benefit from this particularly in my musical activities.

Thank you to my teachers and, above all, to Louis Braille!

Erich Schmid

Musikwoche: Noten, Bilder und Gedanken

Wie versprochen setzen wir heute unseren kleinen Exkurs zur Braillenotenschrift fort.

Für Abwechslung in unseren Bildern sorgt heute außerdem Tânia Jordão Cardoso mit ihrem tollen, zum Event passenden Zusatzbeitrag.

Und damit noch nicht genug:

Für einige von uns war und ist die Braillenotenschrift ein wichtiger Bestandteil ihrer Leidenschaft und ein treuer Begleiter durchs Leben.

Heute lesen wir dazu ein paar Gedanken von Erich Schmid.

Habt ihr vielleicht auch eine ganz besondere Verbindung zur Notenschrift?

Vielleicht hat sie euch ja – wie manchen von uns bei „Braille 200“ – schlaflose Nächte vor einer Klassenarbeit bereitet?

Schickt uns gern eure Erinnerungen und Gedanken an braille200@livingbraille.eu und teilt sie hier mit uns allen.

Jetzt wollen wir euch aber nicht länger auf die Folter spannen und beginnen mit Tânia’s kleinem Bildbeitrag.

Bildbeschreibung:

Das Bild zeigt eine Nahaufnahme der Tasten einer Orgel. Auf dem Notenhalter liegen zwei Seiten mit Braille Notenschrift, und links befindet sich ein Ausschnitt einer alten Standardpartitur. Die Partitur zeigt ein Segment der Zweistimmigen Invention in E-Dur von Johann Sebastian Bach.

Folge 2:

Die Notennamen

Warum ist die Musiknote A eigentlich nicht der Braille-Buchstabe A (⠁)?

Louis Braille hat sich etwas dabei gedacht. Die Notennamen sind aus Zeichen gebildet, die das Quadrat der oberen vier Punkte der Braille-Zelle einnehmen: das sind die Buchstaben D E F G H I und J (⠙⠀⠑⠀⠋⠀⠛⠀⠓⠀⠊⠀⠚).

Die Zeichen, die nur aus den Punkten auf der linken Seite bestehen – also Punkte 1, 2 und 3 – braucht Braille für andere Sachen; wofür, das erfahren wir noch. Die Buchstaben A und B (⠁⠀⠃) gehören jedenfalls zu diesen Zeichen.

Und auch die Zeichen aus zwei Punkten nebeneinander – 1 3, 2 5 und 3 6 (⠉⠀⠒⠀⠤) – braucht Braille für Anderes.

So stehen also die Buchstaben D bis J für die Noten C bis H.

Es wird auch vermutet, das Braille die Notennamen als Do Re Mi Fa So La Ti Do kannte. Und da liegt es auch nahe, der Note Do den Buchstaben D zuzuordnen.

In der Musik sind Töne unterschiedlich lang. Das muss auch in der Braille-Notenschrift ausgedrückt werden. Dafür nutzt Braille die beiden unteren Punkte 3 und 6 der Braille-Zelle.

Achtelnoten haben keinen dieser Punkte. Eine Achtelnnote C ist also der Braille-Buchstabe D (⠙).

Viertelnoten bekommen zusätzlich den Punkt 6. Die Viertelnote C sieht also aus wie die 4 in Computer-Braille (Punkte 1 4 5 6, ⠹).

Eine halbe Note erhält zusätzlich den Punkt 3. Eine halbe Note C sieht also aus wie ein N (⠝).

Ganze Noten bekommen schließlich die Punkte 3 und 6, womit eine ganze Note C wie ein Y (⠽) aussieht.

Und was ist mit 32stel Noten?

Die Punkte 3 und 6 werden mehrfach verwendet: Die ganze Note mit den Punkten 3 und 6 sieht genau so aus wie die 16tel, die halbe wie die 32tel, die viertel wie die 64tel und achtel wie die 128tel.

Ob das Braille-Zeichen Punkte 1 3 4 5 6 (Y, ⠽) eine Ganze oder eine 16tel ist, erkennt man aus dem Zusammenhang: In einen 4/4-Takt passt nur eine ganze Note, aber 16 16tel Noten.

Übrigens: Wie weiß man, wenn ein Takt zu ende ist? Der Taktstrich ist in Braille einfach ein Leerfeld.

Eine Besonderheit ist noch: Wenn viele schnelle Noten (16tel oder schneller) der gleichen Länge nacheinander stehen, muss man nur bei der ersten die Punkte für die Notenlänge hinschreiben, bei den folgenden gleich langen Noten, kann man die Punkte weglassen. In einer Zeit, wo nur mit der Schreibtafel geschrieben wurde, konnte man damit viele Punkte einsparen und es ist auch übersichtlicher zu lesen.

Auch an den Zeichen für Pausen seht Ihr, dass das C nicht der Buchstabe C sein kann.

Die Pausen werden so dargestellt:

Achtel und 128tel = Punkte 1 3 4 6 (X, ⠭)

Viertel oder 64tel = Punkte 1 2 3 6 (V, ⠧)

Halbe oder 32tel = Punkte 1 3 6 (U, ⠥)

Ganze oder 16tel = Punkte 1 3 4 (M, ⠍)

Wäre der Buchstabe C auch die Note C, dann wäre das M eine halbe C, aber es ist eben auch eine halbe Pause.

Eine Sache gibt es, die in Braille wie in Schwarzschriftnoten aussieht: Der Punkt. Ein Punkt nach einer Schwarzschriftnote oder Pause verlängert diese um die Hälfte. In Braille ist das der Punkt 3, der nach einer Note geschrieben wird. Ein C, dass 3 Schläge lang ist, sieht also so aus: N. (⠝⠄)

In der nächsten folge erfahrt Ihr, wie man mehr als nur sieben Töne schreiben kann.

Braillenotenschrift von meiner Kindheit bis heute

Der genialen Erfindung der Brailleschrift und der Braillenotenschrift verdanke ich viele wichtige Impulse für mein ganzes Leben:

In der Blindenschule in Wien wurde ich ab meinem 10. Lebensjahr im Rahmen des Klassenmusikunterrichtes mit der Notenschrift und in Ansätzen auch mit der Harmonielehre vertraut gemacht.

Mein Klavierlehrer war so weitsichtig, dass er mich neben dem Lernen der Stücke nach Gehör auch mit leichten Übungen der Blindennotenschrift für Stücke am Klavier und später auch an der Orgel konfrontiert hat.

Da ich den Beruf eines Musiklehrers anstrebte, kam mir die Kenntnis der Notenschrift sehr zugute, denn mein Ausbildner an der Pädagogischen Akademie kümmerte sich wegen der vielen Studentinnen und Studenten nicht einzeln um mich.

In der Pfarre meines Wohngebietes gab es einen kleinen Kirchenchor und ich wurde gebeten, die Chorleitung zu übernehmen. Diesen ehrenamtlichen Dienst habe ich circa 30 Jahre lang ausgeübt und bald kam auch der Dienst des Kantors für Psalmen und Gesänge während des Gottesdienstes dazu.

Die heutigen technischen Möglichkeiten erleichtern das Übersetzen von Musikstücken in die Braillenotenschrift und davon profitiere ich in meiner musikalischen Tätigkeit besonders.

Danke meinen Lehrerinnen und Lehrern und vor allem Louis Braille!

Erich Schmid

useful links:

Read all articles on: livingbraille.eu

Contact us with your contributions, ideas and questions by: braille200@livingbraille.eu

Social media: Braille 200 on Facebook